Opus Cyprense

- Štikarca

- Jul 30, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2022

Opus cyprense: a myth, collection of works embroidered on Cyprus, particular gold thread, or none of that?

I first encountered opus cyprense in 2021 when I read about opus anglicanum. If opus anglicanum is referring to a set of English-made embroideries from the 13th and 14th centuries essentially embroidered with underside couching and split stitch, does opus cyprense refer to a set of Cyprus-made embroideries with common features?

Well, if this is the case, opus cyprense is hiding commonalities pretty well. Cypriot embroidery workshops are for the most part unresearched, several examples from nearby museums and collections connected with Cyprus are stylistically discordant and scientists disagree about the term itself.

For example, the book European Art of the Fourteen Century simplifies things and mentions that differences between various opuses (anglicanum, cyprense, Romanum…) are based on the use of materials and continues:

“opus cyprense, for example, uses gold thread from Cyprus.” (Baragli, 78)

But then I by chance read about Goldhauben - Golden bonnets in an article from Villach Museum (Petrascheck-Heim pp. 61) (more about golden bonnets in Dr Jessica Grimm blog). There it mentions Cypriot gold, that's great, I think, opus cyprense is made from Cypriot gold.

Cypriot gold or Cypriot gold thread? Oh, joy, you would say, wouldn’t you?

I certainly did and started reading about it even more.

What is opus cyprense?

At first glance, it seems that opus cyprense is a selection of works embroidered in the 13. century with gold thread manufactured in Cyprus and might specifically

»refer to the effect created by embroidered chevrons similar to those seen on the antependium, especially the treatment of the clouds.« (Martiniani-Reber, pp 89)

It is possible that they were also made/embroidered in Cyprus although the Cyprus gold thread was commercially successful and widely distributed resulting in possible manufacture elsewhere (Rome, Sicily). (see Jacoby)

Although Jacoby asserts that Cypriot goldthread was of better quality than others and was valued more, that does not definitely define the origin of work. Miller cites Elster and agrees with her about the origin of works; although it might seem that the opus cyprense was embroidered in Cyprus it may only be a technical term describing embroidery/manufacturing techniques. (Miller, pp. 179) Christiane Elster nonetheless writes that opus is possibly not only a technique of manufacture but also a specific kind of decoration or motive used. In the book Die Textilgeschenke Papst Bonifaz" VIII. (1294-1303) an die Katedrale von Anagni she examined the papal inventories from 1295 and 1311 (where certain embroideries are specified as opus cyprense) and identified two types of motives:

antependiums with Christological motives,

stylized animals, embroidered in medallions or without them.

Furthermore, she mentions base fabrics for these embroideries in white and red (samit) and makes stylistic and technical comparisons with similar works.

Thus she lists several works as opus cyprense:

- Cope made with gold embroidery on samit; embroidered medallions with animals, gilded silver thread couched with silk, silk thread is used for split stitch and satin stitch;

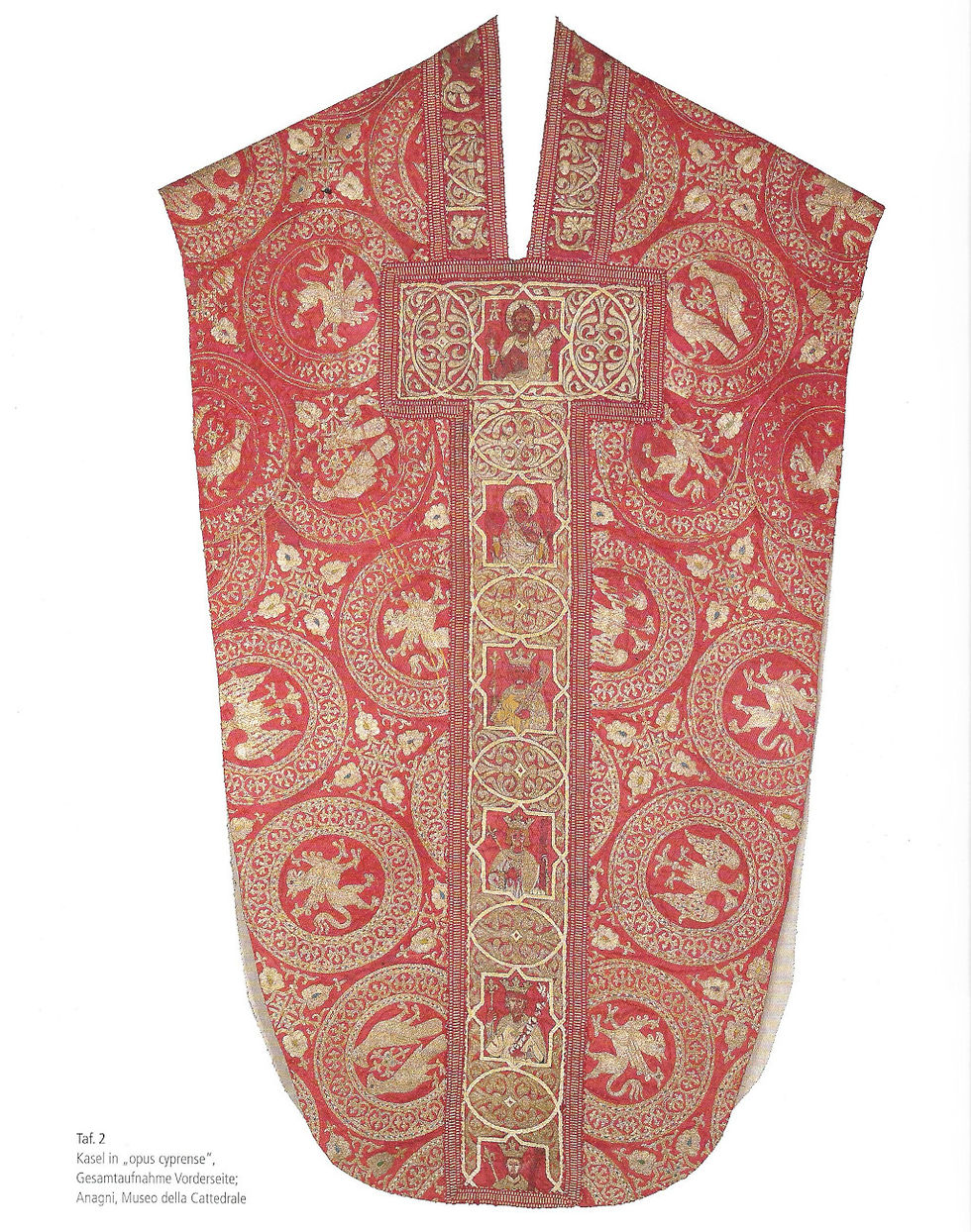

- Chasuble with embroidered figures and flora;13th century embroidered on red samit; later changed; gilded silver thread and silver thread, silk thread;

- Dalmatic with animal medallions; samit fabric; gilded silver thread couched with silk, silk thread is used for split stitch and satin stitch;

and many more.

Comparisons

Stylistically there are connections of Anagni opus cyprense donation with two medallions on the Philip II of Swabia mantle, where there are similarities in medallion forms.

Secondly, she finds similar animal motives, the use of gold threads, the ground fabric of red samite in the reliquary cushion of St Francis in Cortona, the relic bag from Utrecht, and the bonnet of St Stephan in Vienna. All these objects are usually connected with Sicilian workshops. Finally, Elster finds similarities in parrot motive in Anagni and Parrot pluviale from Vicenza.

But only the last two items are technically similar to Anagni's opus cyprense; both use samit fabric as a base and similar techniques. She finds that further technical analysis is needed to confirm the origins.

Furthermore, Elster discerns that there are no inscriptions on any of the Anagni works and neither on the works mentioned above. As a result, it is impossible to determine if they were made in Sicily.

Therefore, she finds it necessary to examine possible connections with Cyprus. Elster confirms that there were workshops making aurum cyprense - gold thread. There is also evidence of workshops making silk fabric and indirect evidence that there were embroidery workshops in Cyprus active in the 13th and 14th centuries. As a result, it seems possible the works of opus cyprense were made in Cyprus.

Not only that, Woodfin even expands on the Cypriot attribution for some works previously attributed to western workshops and suggests Cypriot origin for the Philip of Swabia medallions also. He mentions the medallions and examines their typical Byzantine style and iconography and recognizes that they were made in underside couching. He acknowledges that previous authors connected the works with Palermo on the hypothesis that underside couching was never used in Byzantium, but in his work, he demonstrates that Byzantium also knew and used the underside couching technique of embroidery. On the grounds of new finds, he allows the attribution to a byzantine workshop.

Works from Cyprus

Elster introduces the works below as undoubtedly a product of Cypriot workshops.

Gradson antependium, late 13th century, Bern Historical Museum

The work displays a combination of Byzantine and western characteristics. Woodfin writes about a typical Byzantine enthroned Virgin, and on the other hand, donor embroidered at the foot of the Virgin's throne as a western European element that together with the armorial blazons tells a story of the work. The heraldry connects the work with Oton I Grandson, a knight and crusader that was living in Cyprus at the end of the 13th century after the fall of the city of Acre. Furthermore, Woodfin notes that:

“ The use of Latin and French inscriptions for the Mother of God and the archangels, respectively, also suggests an environment in which Western medieval and Byzantine visual cultures coexisted.” (Woodfin)

Altar frontal with Coronation of the Virgin, 1325, Pisa, Museo dell’ Opere del Duomo

The Frontal is inscribed with the name of Giovanni Conti, first archbishop of Pisa and later archbishop of Nicosia in Cyprus. The inscription dated the embroidery in 1325 when Conti was living in Nicosia. Elster finds that a mix of Gothic elements from the Nothern Alps and Byzantium firmly puts the creation of the piece in Cyprus.

On a personal note, it’s interesting, that Coronation on the Pisa Altar frontal reminded me on the Veglia Altar Frontal. This piece was made by Paolo Veneziano around 1330 in Venice. Like the Pisa frontal, the Veglia frontal is also a mix of western and Byzantian characteristics, but the Christ crowning the Virgin Mary composition is almost identical in the position of the figures on the throne and the position of their hands.

St Mary on the Throne with saints, end of 13th century, Lyon, Saint-Jean Cathedral

Elster describes a small piece with the Virgin on the throne and two saints beside her.

She finds that the three pieces mentioned above, have nothing in common with Anagni pieces in inventories described as opus cyprense. Therefore it is difficult to connect the Anagni pieces with any workshop in Cyprus. Nonetheless, she finds that there are some similarities between the Gradson antependium and Lyon pieces and the description of several items from the papal inventories from 1295. There it describes motives connected with Christ and saints. As well as a piece with scenes from the life of Christ similar to the Pisa altar frontal.

Conclusion

In view of the Elster finds and newer Woodfin contemplations it is quite possible to find similarities between Anagni donations works stylistically similar to Anagni donations, and works made in Cyprus. But let’s see what textile historians find out next.

By the way, the story about connections and similarities can go on and on.

For example: when I researched opus Cyprense I found an article about a lovely embroidery from the Cathedral of Sens in France. Lady Jeanne d’Eu, countess d’Étampes donated it to the chatedral. There are strong similarities between this piece and the Pisa embroidery in the white ground fabric, selection of motives, as well as in mix of eastern and western iconography. Does that mean the embroidery was made in Cyprus?

In short: I still don’t know what opus cyprense is exactly, but it seems nobody has an exact idea either.

What do you think about the pieces? Do you see any similarities?

Works Cited

Baragli, Sandra. European Art of the Fourteen Century. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007. Google knjige, https://books.google.si/books?id=3SUrSKSlpxoC&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=opus+cyprense&source=bl&ots=IWwUuAbYF_&sig=ACfU3U255izZ95BQjV7_LAP9vTqhdBCc_Q&hl=sl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjCueiKkO_4AhVFt6QKHUw9BH0Q6AF6BAgdEAM#v=onepage&q=opus%20cyprense&f=false. Accessed 10 7 2022.

Elster, Christiane. Die Textilgeschenke Papst Bonifaz" VIII. (1294-1303) an die Katedrale von Anagni, Petersberg, Michael imhof Verlag, 2018.

Jacoby, David. Cypriot Gold Thread in Late Medieval Silk Weaving and Embroidery, Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, 2014, https://www.academia.edu/7637562/9_Cypriot_Gold_Thread_in_Late_Medieval_Silk_Weaving_and_Embroidery, Accessed 28 07 2022.

Martiniani‑Reber, Marielle. Le parement d’autel de la Comtesse d’Étampes : une broderie réalisée dans le duché d’Athènes ?, Cahiers balkaniques [En ligne], 23 12 2021, https://journals.openedition.org/ceb/18275. Accessed 10 7 2022.

Martiniani-Reber, Marielle. “An Exceptional Piece of Embroidery held in Switzerland: the Grandson Antepedium.” From Aphrodite to Melusine: Reflections on the Archaeology and the History of Cyprus, 2007, https://www.academia.edu/37690589/An_Exceptional_Piece_of_Embroidery_held_in_Switzerland_the_Grandson_Antepedium. Accessed 17 7 2022.

Miller, Maureen. “A Descriptive Language of Dominion? Curial Inventories, Clothing, and Papal Monarchy c. 1300.” Textile History, 16 11 2017, https://www.academia.edu/36674263/A_Descriptive_Language_of_Dominion_Curial_Inventories_Clothing_and_Papal_Monarchy_c._1300. Accessed 10 7 2022.

Petrascheck-Heim, Ingeborg. “Die Goldhauben und textilien der hochmittelalterlichen Graeber von Villach-Judendorf.” Neuse aus Alt-Villach, Museum del Stadt Villach, 1970, pp. 57-190.

Woodfin, Warren T. “Underside Couching in the Byzantine World.” Cahiers balkaniques [Online], 17 12 2021, https://journals.openedition.org/ceb/18337?lang=en. Accessed 17 July 2022.

Comments